Imagine our world as Hawkins, the small town from Stranger Things, where nature acts as a shield against a real-life “Upside Down.”

In the show, the Upside Down is a dark, decaying parallel world that spreads toxic influence and threatens everything it touches.

Biodiversity loss threatens our reality, shattering the natural systems that sustain us and our health. Clean air, fresh water, food supplies, climate stability—everything we rely on is breaking down.

Humanity faces more disease, food shortages, a harsher climate, and tragedy without healthy ecosystems.

COP16 in Cali brought together scientists, Indigenous leaders, ONGs, policymakers, business representatives, journalists, and other stakeholders for the last in November to confront this crisis.

They were here to defend the systems that sustain us because the stakes couldn’t be higher.

Our forests, oceans, and rivers stabilize the climate, clean our air, and provide food and medicine. But this shield is cracking, and as ecosystems break down, these protections disappear. The loss of biodiversity sends ripples through our water, food, and health systems, destabilizing the resources we rely on every day.

Without action, we’re headed for an environment that’s increasingly hostile to life.

COP16 in Cali was a move to stop this crisis.

Protecting biodiversity may be our last, best defense.

So, what exactly is at risk, and why is nature so critical to human health?

Let’s explore.

Cali: A Biodiversity Hotspot and the Ideal COP16 Venue

Hosting COP16 in Cali, Colombia—a biodiversity hotspot under growing threat—was a powerful reminder that protecting nature is no longer optional; it’s urgent.

Colombia is the second-most (Brazil is first) biodiverse country in the world, with 10% of Earth’s species.

Valle del Cauca, the state where Cali is located, is home to

- 540 bird species,

- 70 mammals, and

- 700 species of plants, many of which are endemic.

When convening in Cali, participants were reminded of the rich biodiversity that sustains global health and stability.

Why Protecting Nature Means Protecting Ourselves.

We’re not talking about variety of species; we’re talking about the foundation of the systems that support life on Earth and provide essential resources for human well-being.

Losing biodiversity disrupts these systems, leading to very real consequences for our health:

1. Diseases new and old:

Untouched ecosystems act as natural barriers, keeping disease-carrying animals safe from human populations.

The book Planetary Health: Protecting Nature to Protect Ourselves, edited by Andy Haines and Howard Frumkin, explores the connections between human health and the state of the natural environment. It provides a good look at how environmental degradation—such as climate change, biodiversity loss, pollution, and deforestation—impacts human health—directly or not.

The research in the book highlights that 75% of emerging infectious diseases—such as COVID-19 and Ebola—are zoonotic, meaning they spread from animals to humans.

The UN Environment Programme and World Health Organization agree with this when saying that infectious diseases—such as COVID-19, Ebola, and SARS—originate in animals and spread to humans, often due to habitat destruction and closer contact between wildlife and people.

The Planetary Health Commission report raised a critical concern about how environmental changes affect food quality and availability:

Climate change is expected to reduce crop yields, especially in tropical and subtropical regions, in the coming decades and even in temperate areas later on.

2. Less Clean Water and Air:

Forests, wetlands, and grasslands act as natural filters, purifying water and air—resources essential for human health.

In Colombia, the Andes mountains and Amazon rainforests help regulate air and water quality locally and globally. When these ecosystems are degraded, we lose these vital services, leading to health issues like respiratory diseases and waterborne infections.

3. Food Insecurity:

While increased carbon dioxide helps some crops grow faster, it also reduces their nutrient content, lowering essential micronutrients.

Meanwhile, pollinators are declining worldwide due to environmental shifts, impacting the yields of crops that depend on them. Lower fruit and vegetable availability could lead to an additional 1.4 million deaths per year, raising risks of non-communicable diseases and infections linked to nutrient deficiencies. Without biodiversity, crop failures and food shortages could become the norm, putting millions at risk of hunger.

4. Loss of Medicinal Resources: Nature is a treasure trove of medicines.

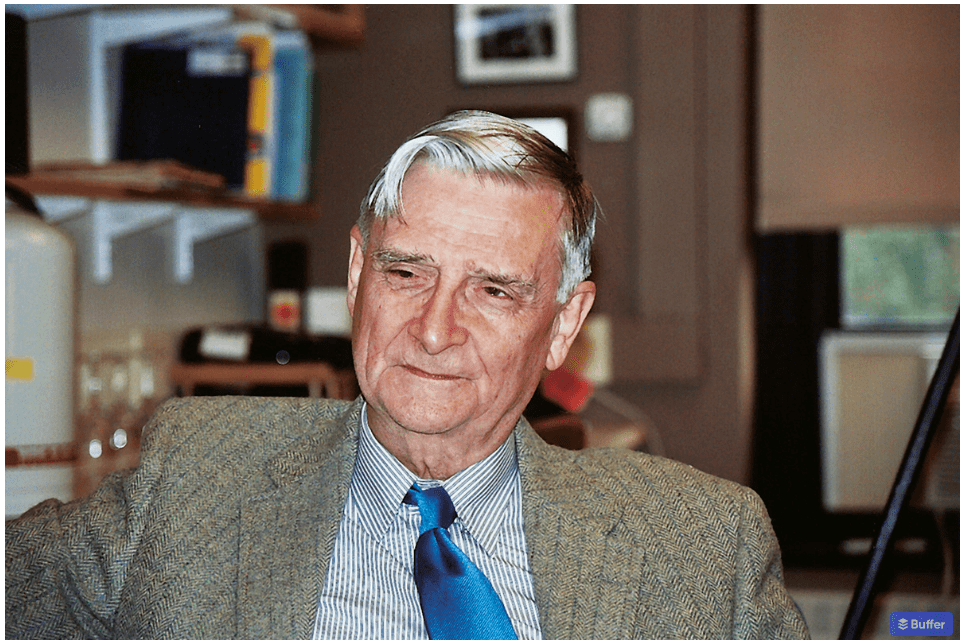

Biologist E.O. Wilson famously said, “Destroying rainforest for economic gain is like burning a Renaissance painting to cook a meal.”

Many of our remedies, from cancer treatments to antibiotics, come from compounds found only in diverse ecosystems.

As we lose species, we may lose potential cures for diseases that could save countless lives.

Indigenous Guardians: How the Nasa and Embera Protect the Earth—and Us

The Nasa, based in Cauca and southern Valle del Cauca, and the Embera, rooted in Colombia’s Pacific region, have long protected their territories—not just as land, but as living extensions of their culture and identity.

At COP16, their voices were acted upon.

A permanent body was established to ensure Indigenous knowledge shapes global biodiversity decisions.

Alongside this, the newly created ‘Cali Fund’ guarantees financial resources for Indigenous-led conservation projects, with a significant share dedicated to meeting their self-identified needs (Forest Peoples Programme, 2024; Transformative Pathways, 2024).

But these victories aren’t just policies on paper—they’re reinforcements for work already in motion:

The Nasa employ traditional ecological knowledge to care for their forests and rivers. They cultivate native plants like yarumo (Cecropia peltata) and guava (Psidium guajava), which naturally enrich the soil and regulate water cycles. These trees prevent erosion and support entire ecosystems (Forest Peoples Programme, 2024).

Meanwhile, the Embera grow medicinal plants such as Calaguala (Polypodium leucotomos) and Achiote (Bixa Orellana), used for respiratory health and skin protection (El País, 2024).

Both communities remain on the frontlines of resistance against illegal mining and logging, ongoing threats to their territories (El País, 2024).

The Nasa’s unarmed Indigenous guards patrol their lands, embodying a proactive approach to conservation that safeguards not just their homes, but global biodiversity (Forest Peoples Programme, 2024).

Their commitment goes beyond protecting their lands—it contributes to a larger, global effort to sustain the balance of ecosystems we all depend on.

Nature is slipping away—will world leaders finally act before it’s too late?

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, adopted at COP15, aims to set things right by 2030.

It sets ambitious goals, including protecting 30% of the world’s land and water.

But only 10% of countries have submitted updated biodiversity action plans. Only 33 percent have partially updated their national targets.

My jaw dropped to the floor and hasn’t bounced back when I read this.

This sloth-like response can sabotage the whole initiative.

Take a look at this article from The New York Times.

It gobsmacked me.

And take a look at what co-author of the book Net Positive: How Courageous Companies Thrive by Giving More Than They Take, Paul Polman had to say about what he saw on COP 16:

The costs of inaction are now far greater than the cost of action. Failing to act on climate would cost the world $178 trillion by 2070 vs. $43 trillion in benefits that can be realised by acting.

This is even more pronounced in nature than in climate – where investments can deliver faster and starker results. $1 spent on nature restoration yields $9 in economic benefits, and we know that we cannot solve the climate crisis without solving the nature crisis.

Frankly, it was surprising to see how few CEOs were at the summit when this issue is perhaps the most critical that we face.

Without comprehensive action—or really, any action at all—we risk accelerating our downfall.

The world is dying, period.

We need to close the gate on biodiversity loss before it’s too late.

Like the heroes in Stranger Things, we face only one choice: guard the ecosystems that sustain life on Earth.

There’s no other way.

The whole world must work together to do just that. Because without real action, the planet could become a version of the “Upside Down.”

COP16 was the move to do something for the biodiversity that keeps our planet alive—for us and for the future.

Let’s hope it’s more than just howling into the wind.

Because it’s now or never.

References

1. World Wildlife Fund, New Analysis Reveals Countries Are Falling Short on Nature Pledges Ahead of COP16, September 2024. [Link].

2. Living Planet Report 2024, WWF. Detailed analysis of wildlife population declines globally and regionally.

3. The Lancet, Health and Biodiversity Loss: How it Affects Human Health, 2024.

4. Planetary Health: Protecting Nature to Protect Ourselves, Overview of the interconnectedness of biodiversity and public health.

5. NBSAP Tracker: National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans, WWF, 2024. Link

6. The Rockefeller Foundation-Lancet Commission on Planetary Health, Safeguarding Human Health in the Anthropocene Epoch, Public Health Reviews, 2015. Link

7. Forest Peoples Programme, Outcomes of COP16 for Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities, 2024. Link

8.Transformative Pathways, Outcomes of COP16 for Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities, 2024. Link

9.El País, Cali recupera Los Farallones, su emblemático parque natural asediado por la minería, 2024. Link